I was born in 1970 and spent my early years on the island of Feydhoo. My family lived in one of the old British built houses. It had one room. We had no electricity, clean water, sewerage system, medical doctor or even proper schools. There was mum, dad, four brothers and two sisters. I was the second youngest.

Despite its plainness, our family home was a happy place, with entertainment provided by our every energetic sibling.

Like every Maldivian, many of my first memories are of the sea. I remember friends showing me how to fish, casting from the beach. I used to love bodyboarding. I didn’t have a proper board, making do with a plank of wood left over from the neighbor’s house repairs. As well as fun, the sea was also a source of tragedy for our family, when, on 29th November 1971, a boat carrying a group Island picknickers, including my two sisters (Fathimath Didi 17 years and Mariam Didi 10 years and my brother Hussein Saeed 6) capsized. Twenty people died in the incident, including my sister Mariam Didi. It left a lasting impact on the family.

My father worked for the British Army as a waiter and kitchen hand. He was an inveterate learner, spending all his spare money on books. He taught himself English, Arabic and Urdu, and subscribed to the Reader’s Digest and a serialized encyclopedia. He became a reference point for the men of the island, and we would often fall to sleep to the murmur of my father’s voice, giving advice to visitors. Father was also known locally as a moral person, values that he instilled in his children from an early age. (Safekeeping of money)

This passion for learning was to become a central part of our own lives, but not until after tragedy struck again. In 1979 my father died. Rudimentary level of medical care on the island, and indeed, throughout country meant his condition went undiagnosed. My mother now had to raise the children alone. It was a tall order, but she did the best she could, earning extra money by cooking for public holidays and festivities to supplement our diet. But my brothers and I, without dad to keep us in check, were at risk of becoming tearaways, getting ourselves into all kinds of scrapes.

Fortunately, before father’s death he had saved enough money to send his eldest son, Abdullah Saeed (now a professor at University of Melbourne), away to Pakistan to get an education. Later he obtained a scholarship at Madina University, Saudi Arabia and now saved his pocket money and sent home to pay for his younger brothers’ education in Pakistan. His continued support, guidance and oversight was instrumental in my educational and professional life. I owe him so much. It was a hard decision for our mother to let us go, but she too saw the value of learning and was worried about what would happen to the boys if they continued without proper guidance.

Arriving in Pakistan was a real culture shock for me. I was then merely 10 years of age. But found learning easy – very likely inherited from father.

Haaji Abad (in Faisal Abaad, Pakistan) could not have been more different to my hometown Feydhoo. Nine students shared one tiny room. We had two meals a day – 2 Naan and Dhaal curry for morning breakfast and 2 Naan and One curry (often vegetable or beef or lamp) for dinner. The only time we got fish and Biriyani were during Eid holiday! Otherwise, meals were very much set. It never changed during my 6 years stay at Salafia.

The Madarasa then had a good number of Maldivian students. Many of them from reasonably well of families. They would often receive letters and parcels from post. I was among the poorest. So, postal packages or money from family wasn’t in my contemplation. For me a rare letter from home or from a family member or that of a friend was just as good.

Most challenging aspect of Pakistan was there was no heating systems or hot water! Imagine taking cold showers in the middle of winter when the temperatures were close minus degrees! But we did it daily to the astonishment of our Pakistani friends. Maldivian students were reputed for their clean, neat, and good hygiene standards.

The ultimate dream of all students at Madaras was to get enrolled into any of the religious institutes in Saudi Arabia. I was offered one but declined. I was particularly interested in gaining a western style education, seeing nothing incompatible with the two disciplines. To this end I studied English with the assistance of my roommates and friends.

One thing that struck me about Pakistan at that time, and has stayed with me, was the way that, even in a military dictatorship, dissent was still tolerated. It was not unusual to see colorful protests, to hear people decrying the government in the streets or to read a variety of opinions in the press. I found this atmosphere of free expression was healthy and encouraged civil awareness. I was in the crowd when Benazir Butto (later to become the Prime Minister) returned to the country in 1987. I too was caught up in the buzz of excitement, but also the sense of danger around her.

I was, in own way, a dissenter too. I would encourage other students to join me in refusing some of the more menial work at Madarasa, considering it exploitative, though it may also have been an excuse to watch the cricket! Of course, there was no television in the students’ rooms so we would have to watch in coffee shops until chased away.

Wanting to widen my education, I applied for and was admitted to the International Islamic University of Malaysia. Without any funding though, it was going to be a tough few years. With borrowed money from friends, I purchased a one way ticket to Kuala Lumpur and USD100 in pocket I left to Malaysia. On arrival I was lucky enough to gain a grant from the World Islamic Call Society. However, this amounted to just 150 Malaysian Ringitt a month (around $20). Later I was able to secure the University and the Government of Maldives’ scholarship award. Although I now slept in a dormitory with 16 other students, they had much more space than at the Madrasa. The beds didn’t even touch each other!

It took me a while to adapt to university. Before I could really begin my studies, I had to master English. This I did by sitting everyday with the English newspapers and an English-Urdu dictionary, reading and rereading until, eventually, I could understand the whole paper. It was this intense period of reading along with my later studies that led to my deteriorated eye condition.

I thrived at university, throwing myself into my studies. I excelled in class and practically lived in the library – often reading books and magazines that had nothing to do with my course. It was in the library that I met my future wife, Fatin. She was a dedicated student. We were married four years later.

After completing my Masters in comparative laws, I returned to the Maldives to work as a state attorney at the Attorney General’s Office. I had been back twice before, just for short trips, and on each occasion, I was struck by the dramatic changes at home. Most noticeable was the spectacular pace of development. I had left my island Feydhoo by boat reaching the Capital Male’ in three days and three nights but returned to the Island by an hour thirty minute flight. The paved streets and new high raise buildings of the Capital were impressive as was the introduction of electricity and proper schooling to Feydhoo.

At work, though, I noticed that in terms of the legal system, at least, the Maldives was not progressing fast enough. I was shocked to discover the incredibly high conviction rate. This, the public was told, was a sign of the court’s efficiency, but that was not the case. Rather it was a sign of the culture of the courts, with judges convicting even with insufficient evidence for fear of losing their jobs. I became aware, for the first time, of the all-pervading influence of the government in the legal system. As a state attorney, there was little I could do except try to persuade the judges I knew to follow the evidence on each case, rather than dictates (actual or perceived) from the top.

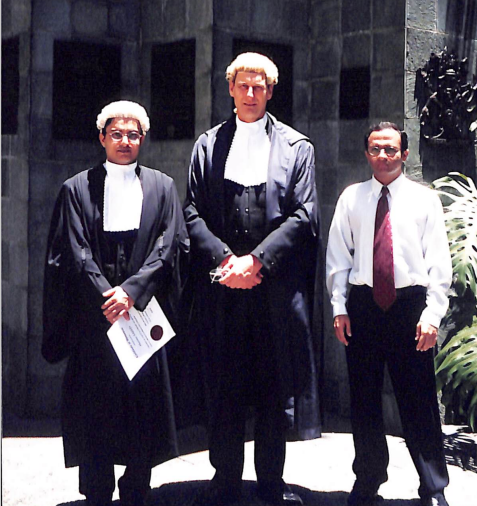

Sensing that it might make me more influential at home and contribute more effectively to the system, I jumped at the opportunity to complete my PhD in Queensland, Australia in 1998. This came when my wife Fatin was awarded a Malaysian government scholarship to pursue her own Ph.D. Initially I joined her under dependent visa. Once again it was a struggle to finance my studies. This time I had to work. At first, I struggled to gain employment, but after completing a professional hospitality course, I worked as a kitchen hand and served food in various restaurants.

I later worked as a research assistant at the University of Melbourne and a tutor and a lecturer at the University of Queensland before receiving a partial scholarship from the University. But the bulk of income came from the funding Fatin received from the Government of Malaysia.

On completing my studies in 2002, I immediately wrote a letter to President Gayyoom offering my services. To my astonishment, the President called me to thank for my offer and invited me to join the government. I told the President that the government will have to pay for my accommodation as rent in the Capital Male’ then and even now remains several times higher than average civil servant’s salary. My reasons were simple – I wanted to focus on the job, avoid being beholden to the rich, or end up doing multiple jobs or asking favour from people. The President agreed honored his commitment even when I was a cabinet Minister. I thank the President for that.

Shifting from Malaysia to Male’ was hard. Fatin and I were living on her tutor’s meager salary then. I didn’t have money. Two close friends helped me – Mr. Hassan Zareer and Mohamed Shaweed. The former was few years senior to me, and we study in Pakistan and in Malaysia together. I always looked upon him as an elder brother. Shaweed was a happy going young fellow befriended during Malaysian student life. I am so much grateful to their support.

I started my new life in the Maldives with the role as the Chief Judge of the Criminal Court and the Juvenile Court. Few months later Fatin also came to Male, but not before some negotiation with her employer – the Malaysian Government. The funding she received was conditional on her teaching on her return. We were unwilling to be parted again, so we had to agree to pay back the money. I received several offers of support from Maldivian businessmen but felt it unwise to owe favors. We negotiated an arrangement with the Malaysian government to pay back the money monthly, a commitment we only managed to complete in 2017.

My new role in the Maldives was as the Chief Judge of the Criminal Court and the Juvenile Court allowed me much more scope to change the system. I wasted no time. One of my first discoveries was that 97% of prosecutions and convictions were secured on the evidence of a confession alone. Many defendants complained that confessions were obtained through beatings and intimidation. Furthermore defendants who attempted to retract confessions were charged with perjury.

I started to compile information where prisoner abuse was suspected or alleged. The same policemen’s names recurred again and again, under the same circumstances using the same methods. The evidence was damning.

This was far from the only problem in the legal system. There were no rules of disclosure, rights to legal representation, no guidance on appropriate sentencing. I pushed for reform in all these areas, with significant achievement, but all too often I was met with resistance. This was the way things were done, I was told, and the higher officials did not want change.

Infuriated by the slow rate of progress, I compiled a report on the problems with the country’s criminal justice system and, obtained an appointment with President Maumoon Gayoom. At the meeting, the President listened to me for just five minutes before asking me to be the new Attorney General. It turned out that the President had booked the appointment to offer the new job, not to listen to what I had to say. I agreed but made it clear that I would only continue in the job as long as I felt I was able to fulfill my duties free from interference. The president didn’t know what he was letting himself in for.

It was around this time, just before I became Attorney General that my mother passed away. Although deeply affected by this further loss in the family, I could only allow himself a brief break from my work.

On starting in my new role, I immediately began a process of reform of both then legal system and looked to a wider program designed to foster a culture of fairness before law and democracy. Quick change was achieved on the right to legal representation, disclosure of evidence, court rules, bail system, habeas corpus and retraction of confessions. But this was just the beginning of my ambition. I felt that as so much of the system was rotten that to change things piecemeal was not enough, and a more radical approach was needed.

At this time amongst the people and also within certain areas of government, there was a growing movement towards a total overhaul of the state, to make it more open and democratic. This was well in line with my own agenda, and he soon found allies with figures such as the then Foreign Secretary Dr. Ahmed Shaheed, Information Minister Mr. Mohamed Nasheed and of course with old friend, the then Justice Minister, Dr. Mohammed Jamil. We, and others, formed a group within the government to push a reform agenda called New Maldives.

The Maldivian Democratic Party (“MDP”) and other opposition groups were also pushing for change, but I was wary of their calls for a violent overthrow of the president and the damaging call for an international boycott of the tourist industry. Moves like these had, I felt, catastrophic potential for a nation that relies on tourism, international reputation and imported goods. While their intentions were good, their policies were short-sighted.

With the release of the Roadmap to Democracy in 2006 the New Maldives movement had a clear agenda, and as Attorney General I made significant progress along that road. This included the introduction of political parties, ending the persecution of writers and reporters, and steps to strengthen the independence of the judiciary. But as time went by it became more and more apparent to me that, while appearing to endorse the reform progress in public, President Gayoom himself was behind endless moves to block it.

These moves included a refusal to replace top police leadership, replace the incompetent Chief Justice, blocking the progress of investigations into corruption and illegal activities in government, stalling of the Roadmap for Democracy and take steps to address religious extremism. Things finally reached a head in August 2007 when as I had promised from the start, when I was no longer able to fulfill my duties free from interference, I resigned from Government.

It had become clear to me that I had achieved all I could in office. The principal obstruction to reform was no less than the President himself. If true fairness and democracy is to be achieved, I realized, then a new leadership would have to be in office.

I decided to stand as a candidate in the presidential elections in 2008 because I believed that, not only is a change required, but that it must be a meaningful change reaching all corners of our society, implemented by a team that knows how to achieve it.

I, like many Maldivians, had a tough childhood filled with adversity, and I knew the problems that the people of this country faced trying to get ahead. I worked hard to get to where I was in life, not through privilege or cronyism or family connections. In my life it was being provided with the opportunity to succeed that made the difference, and I believed that all Maldivians have the right to such an opportunity.

In the Madrasa, and later, I learnt the value of true faith. As someone familiar with Islamic scholarly work and a true believer, not just an empty figurehead, I believed that I could and would bring true Islamic Democracy for the country to be proud of and as an example to the world.

As a known reformer, who had achieved real change in my time in office, and as a man of principle who left when that change became impossible, I believed that I could be trusted to deliver the fair society we deserve.

As young man, with experience of governance, I was both progressive, forward looking and stable and safe, aware of the unique needs of the country and its people.

I was not in debt to big business, had no relatives in politics, was not a member of a political party. Unlike Gayoom and other politicians, I was free from the taint of corruption and suspicious connections. I had no hidden agenda. The only people I was beholden to are the Maldivian people.

In the election I secured the third place. President Gayyoom and Nasheed of MDP went on to contest in the 2nd round of election. I backed Nasheed and helped him to become the country’s first ever democratically elected President. He appointed me as his Special Advisor. Never sought a single advice nor heeded any I gave. I resigned when Nasheed started democratic reversals. When he resigned in 2012 and his successor Dr. Waheed (who was Nasheed’s Deputy then) appointed me as the Special Advisor. I was able to play very important roles with far reaching political economic and geopolitical consequences [details to be discussed later].

In 2013 Presidential election I partnered with Honourble Qasim Ibrahim and felt barely 2000 votes short to qualify for the second round of election. President Yamin went on to beat President Nasheed.

Shortly after that I left politics and have remained clear of politics and politicians.

Through this blog I intend to write the historical account of events I witnessed.